Marie-Therese Luger writing a preview of an auto-curated assemblage of public memorials in the landscaped heart of the city.

Crossing the bridge to Djurgården, taking a sharp right at Nordiska Museet, a sharp left at Vasamuseet, leading across a currently very empty tourist parking lot lies Galärvarvskyrkogården. This cemetery was established in 1742 and was the last in a series of landscaped cemeteries for naval use. There, gravestones stand in line like a little army of opaque showcases. Golden letters do not only mark the names of those laid to rest here, they also state their ranks and positions in work and society. Here rest, amongst others, Konteramiraler, Viceamiraler, Kommendörer, Kaptenkonsuler, Amiraler, Sjökaptener, Kommendörkaptener, Löjtnanter, Flaggskeppare, Marinpastorer, Flaggtorpedmästare, Förvaltare, Poliskommissarie, Fänrikar i Flygvapnet, Borgmästare, Hovsångerskor as well as ”min älskade make”.

A variety of collective monuments and memorials can be found here as well. One of them, Vasagraven, is commemorating the sinking of the ship Vasa – which itself has found its final resting place at Vasamuseet, only a stone´ s throw away. Vasagraven is a little grove featuring a stone and an anchor resting upon it. The ground of the cove is paved with stones that were used as ballast on the ship. This is pointed out by a small sign on the floor and feels like the beginning or just the remnants of artistic or design-based conceptual thinking.

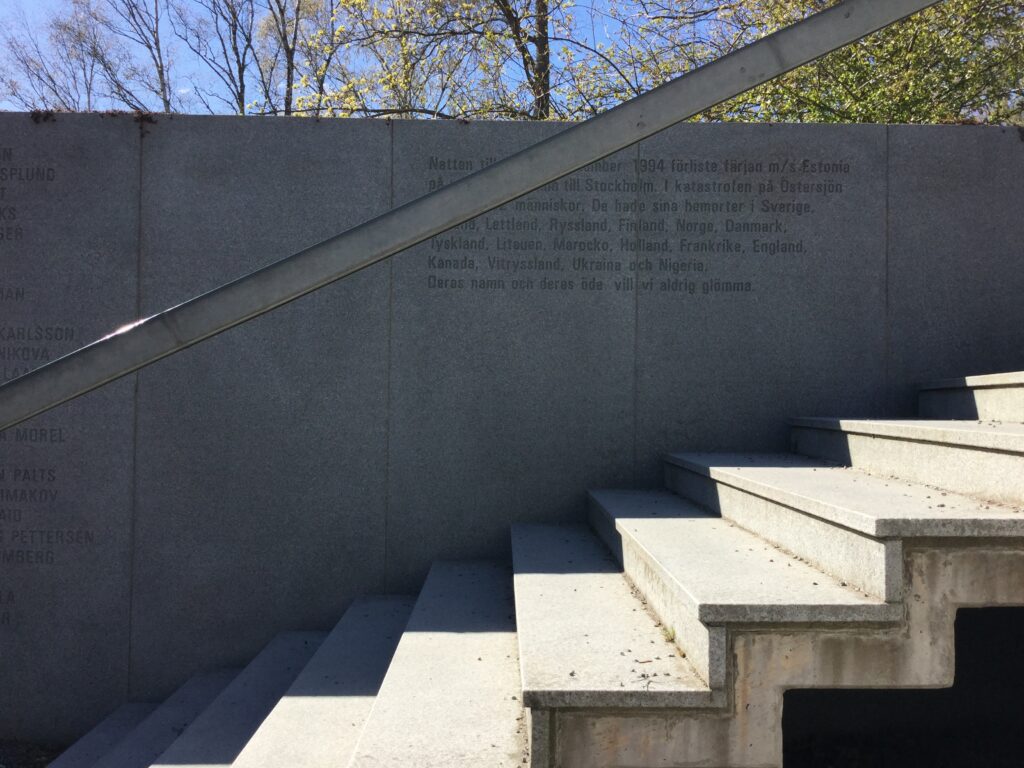

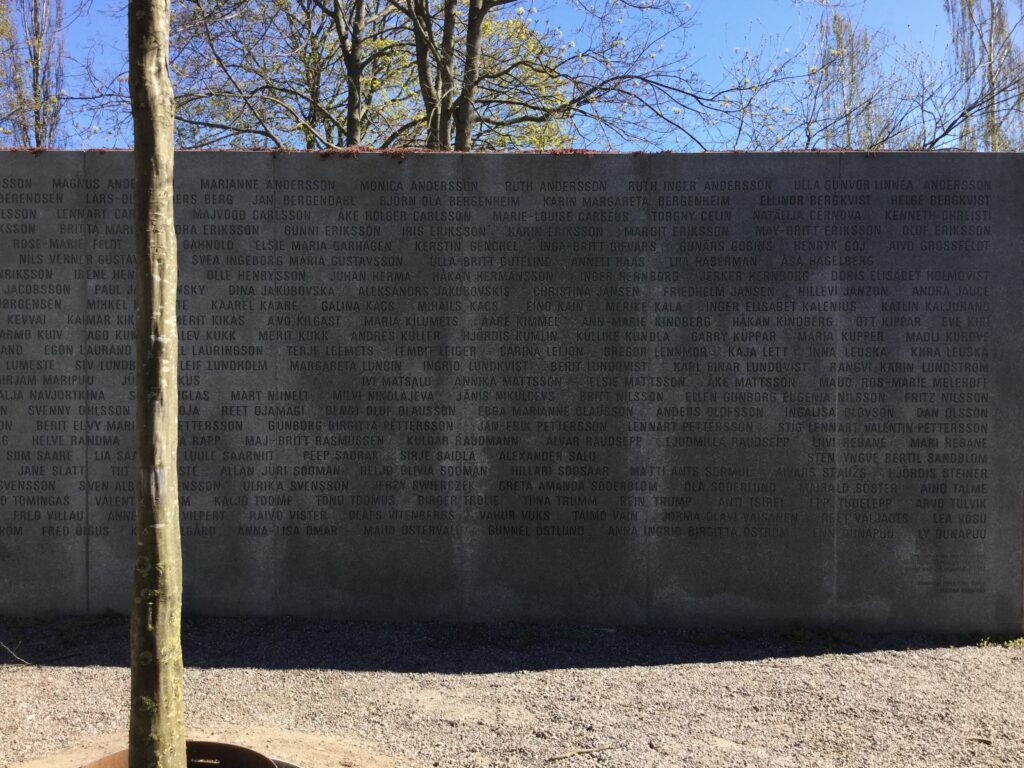

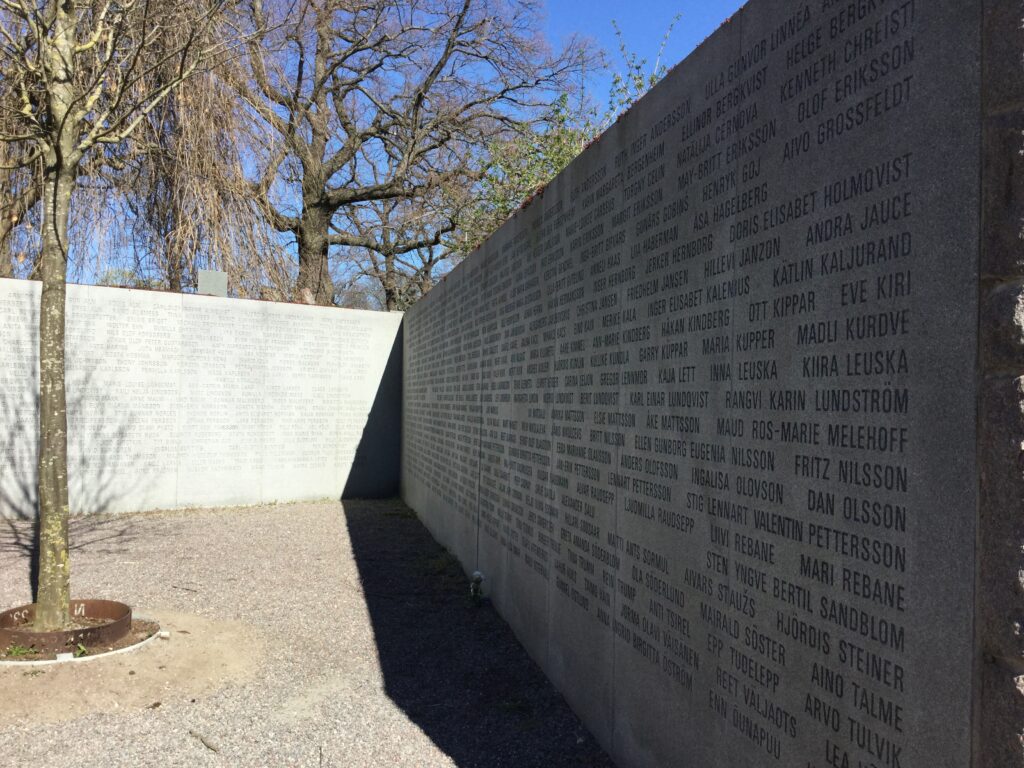

Not far from this cove another memorial has taken shape. It is dedicated to 815[1] persons that lost their lives during the sinking of the M/S Estonia in 1994 in the Baltic Sea. The triangular granite-construction called Estoniamonumentet designed by artist Miroslav Balka can be reached from the graveyard as well as from the waterside, offering two quite different moments of approach and meaning-making. Accessed from the sloping topography of the cemetery a set of concrete stairs leads down to the memorial. Above the stairs: a short descriptive text about the tragedy and the trajectory of the place itself, to be read as one descends into a space that is defined by the walls around it. The walls are engraved with the names of the deceased, the center is marked by a tree planted within a metal band bearing the coordinates of the catastrophe. The walls ahead do not meet to form a corner, but instead create a portal – a non-space – that evokes thoughts of Jonas Dahlbergs unexecuted ”Memory wound” planned for Utøya. The opening gives view to the nearby water – something that feels needed and appropriate. Further, if the memorial is approached from the waterfront the granite walls bear resemblance to the hull of a ship.

Balkas work appears pragmatic in its conceptualization and humble concerning its functionality. The text above the stairs does not mention the artists name and sets the tone for what the memorial should accomplish: remembering the names and the fate of those who went down with the ship. The tree – at the time of writing the original specimen has been replaced with a younger bedding plant – is the only thing that seems ostensible at first sight: Symbolism for hope and renewal after tragedy? Integrative measure for a tree that has since then disappeared and had to be replaced? A nod towards the topography of Djurgården or the proximity of land and sea – life and death, an assumed (but no necessarily accurate) segregation of natural forces?

This conceptual dissonance is caught and cradled by reality, as it is not the only plant to be found in this square: A little vase with flowers has been placed under one of the 815 engraved names, bearing witness to not only those who have disappeared, but those who were left behind.

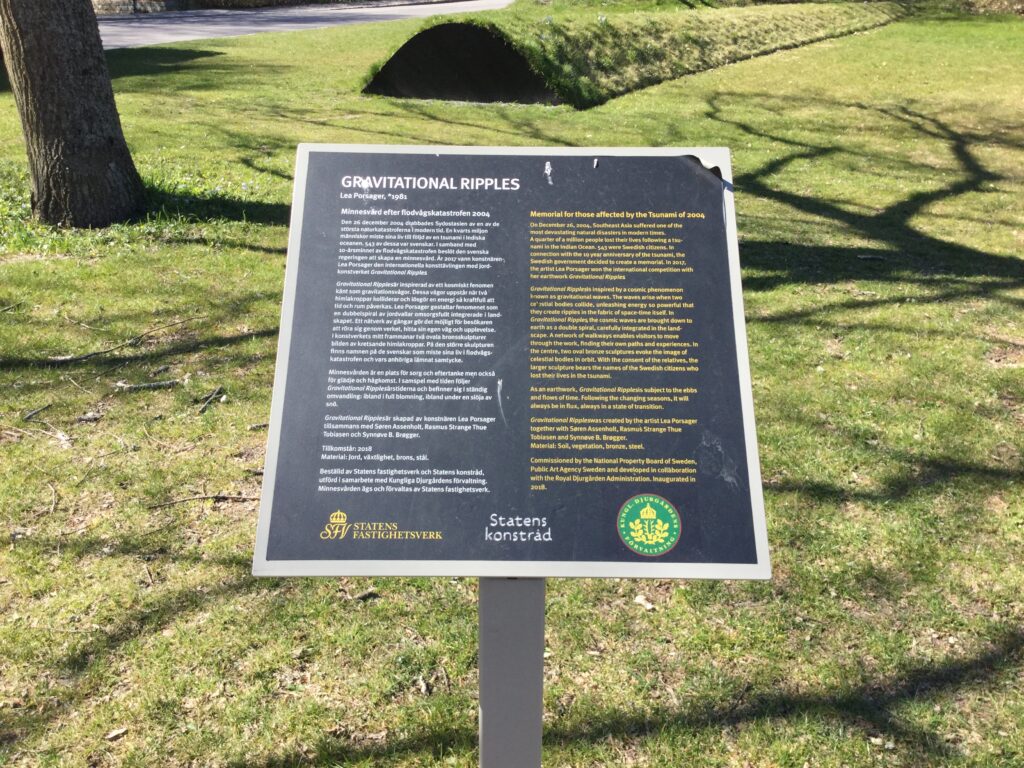

On the opposite side of Djurgården artist Lea Porsager has created yet another memorial for victims of a water-related catastrophe: Gravitational Ripples, a complex piece of public sculpture dedicated to 543 Swedish citizens that lost their lives during the 2004 Tsunami catastrophe in South East Asia.

Form and concept of the work are inspired by a complex phenomenon: gravitational waves. According to NASA, gravitational waves are invisible, yet incredibly fast ripples in space. These waves squeeze and stretch anything in their path as they pass by. Gravitational waves are caused when a star explodes asymmetrically, when two big stars orbit each other or when two black holes orbit each other and merge. Porsager herself cites this as a metaphor for the shock and trauma created by tragedies. On the homepage of Statens Konstråd the work is described as an effort of bringing this phenomenon down to earth.

As a physical entity, Gravitational Ripples is indeed earthbound – and easy to miss. Piles of soil – varying in height – form a structure of fragmented rings leading to an inner core jeweled by two layered bronze plates, one of them bearing the names of the deceased. To ”get” the whole picture the construction must be viewed from above. As a space, Gravitational Ripples aims to let visitors generate their own and diverse experiences by walking through the site – not unlike a classic labyrinth. The complexity and plurality the work offers unfortunately becomes its biggest weakness. This becomes apparent when reading through a descriptive text that is placed on two assumed points of entry to the work. Without this textual guidance the work could just as easily be interpreted as utilitarian landscape design, a Celtic tomb or an abandoned trench. A play on this associative freedom would have enabled a richer experience than the effort of forcing a cosmological phenomenon down to earth.

While the bodily experience of walking through the ripples – cut into pieces by Dahlbergian non-spaces similar to those observed in Estoniamonumentet – works in order to evoke a humble experience of memory, everything else seems unnecessary. The text, explaining the artists thoughts and the concept, falls short of perception. Information about Porsagers collective way of working, as well as inspiration from feminist theory and a conscious interaction with nature (and not against it) is crammed in – all ironically contrasted by the adjacent public toilets: Just in case ”nature” should call – to be washed away by water in swirls. It is not necessarily the concept or the artistic intention that has failed – it is a siege on the dichotomy between human and nature that is muffled by the confinement of human as well as spatial pragmatic realities. Gravitational Ripples simply wants too much – and instead of doing it, keeps explaining it.

Galärvarvskyrkogården, Vasagraven, Estoniamonumentet and Gravitational Ripples can be experienced during a walk around Djurgården – and can as such be performed as a subjective curatorial whole. The sites can be read as different stages of approaching the commemoration of disaster and loss from stones to cosmos. But they can also be read as a parable of the conceptual artist´ s (and as such in elongation the curator´ s or the exhibitionproducer´ s) role in meaning-making. Especially when the meaning that is to be made is not one of canonized knowledge, but one of – very versatile – experience: From the simple mentioning of name and occupation to the overly complex and metaphorical translation of loss into an artistic project. Memorial sites and monuments can be an appropriate base to return to and think about, since their purpose is as simple as it is profound. To accommodate these experiences in a way that is – physically as well as mentally – accessible for a variety of onlookers is the challenge that both memorials as well as curated exhibitions share and constantly need to work towards.

Marie-Therese Luger

M-T L. Works as a curator and researcher. She sometimes writes.

[1] 852 lives were lost, but not all families of the deceased did give their consent to their names being part of the memorial

Recension

Åsikten i texten är skribentens egen. Utställningskritik förbehåller sig rätten att korrigera text i efterhand vad gäller språkfel. Övriga rättelser läggs till som kommentar under artikel.

Vasagraven på Galärvarvskyrkogården

Galärvarvskyrkogården – Djurgården, Stockholm

Permanent installation

Stockholms Stad & Kungliga Djurgårdens förvaltning

Estoniamonumentet

Galärvarvskyrkogården – Djurgården, Stockholm

Permanent installation

Konstnär: Miroslav Balka

Statens Konstråd, Kungliga Djurgårdens förvaltning

Gravitational Ripples

Djurgårdsvägen 266

Permanent installation

Konstnär: Lea Porsager tillsammans med Søren Assenholt, Synnøve B. Brøgger och Rasmus Strange Thue Tobiasen

Statens Konstråd, Kungliga Djurgårdens förvaltning, Statens fastighetsverk